In the end, the crumbling Bywater manor was a home fit only for birds. Doves, poignantly enough.

Eventually, they, too, were shooed away, and the wrecking ball was brought in.

By then, the two-story Creole-style plantation house overlooking the Mississippi River from its perch at Chartres and Mazant streets was far past its prime, having crumbled into ruin after years of neglect.

But in the 129 years it stood, the old Olivier manor served New Orleans well.

It was built as the centerpiece of a sugar plantation, but it served that purpose less than 20 years. For more than a century afterward, it was a place of refuge and mercy for some of the city’s most vulnerable.

It would also be the beacon that called two notable Catholic religious orders to the city — the Brothers of Holy Cross and the Marianite Sisters of Holy Cross — and, after its demolition, as a rallying cry for appalled preservationists that still echoes today.

Not to be confused with the Olivier House on Toulouse Street, the Olivier plantation house was built around 1820 by the Paris-born planter David Olivier.

Occupying the block bounded by Chartres (then Moreau), Mazant, Royal and France streets, the two-story main house was surrounded by a wraparound ground-floor arcade and, supported by rows of stately columns, a second-floor gallery. Both would have facilitated breezes blowing in off the river.

An open, ballroom-sized attic served as a Crescent City crow’s nest, with its dormer windows — facing outward in each direction — offering views stretching for miles.

Original outbuildings included a stable, a detached kitchen and two pigeonniers near the property’s rear.

Although some accounts suggest it ceased being a working plantation due to the Civil War, a city directory shows Olivier sold the property far earlier; by 1838, it was housing an “institution for young men” run by Louis Caboche.

It didn’t last. By 1840, creditors forced the sale of the property. The eventual purchaser: the New Orleans Catholic Association.

And that’s where its second life really began.

A view of one of the fireplaces in the old Olivier Plantation House.

A yellow fever refuge

In August that year, amid regular outbreaks of yellow fever, cholera and other infectious diseases, the association moved residents of its “bayou asylum” — an orphanage on Bayou St. John — to the old Olivier property.

It was effectively the start of St. Mary’s Orphan Boys Asylum, which would become known to generations of New Orleanians as St. Mary’s Orphanage.

Initially, St. Mary’s was run by a secular board. Then, in 1848, New Orleans Archbishop Antoine Blanc invited France’s Congregation of Holy Cross to assume oversight duties. It would send five brothers, marking the introduction to New Orleans of the Brothers of Holy Cross, the order that later founded Holy Cross School.

Joining them were the city’s first three Marianite nuns, a separate order but part of the same Congregation of the Holy Cross religious family. They, too, would later go on to found local schools, including Holy Angels Academy in the Bywater and Our Lady of Holy Cross College (now University of Holy Cross) in Algiers.

In 1871, the Marianites took over sole control of the orphanage, a duty they would hold for 61 years. In that time, it would grow to include additional buildings, including a Gothic chapel erected in 1891 to replace a wood chapel near the corner of Chartres and Mazant.

A brick wall surrounding the block created the feel of a proper campus — but also hid the old original Olivier house from view for decades.

Shuttered and sold

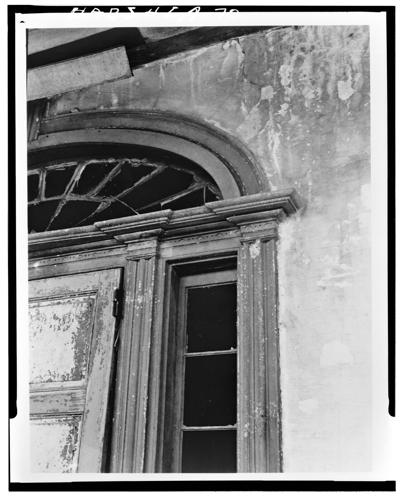

A detail shot of the inside of the main entrance to the old Olivier plantation house, including its fan-shaped transom.

By 1932, with medical science contributing to a decline in the city’s orphan population, the Chartres Street property — home over the years to an estimated 9,000 orphans — was shuttered and sold.

Its role as a place of mercy, however, continued, with the Olivier property serving in the early 1930s as a homeless shelter run through the federal government’s Depression-era Emergency Relief Administration, a predecessor to the Works Progress Administration.

By the 1940s, with the Depression over but World War II on the horizon, it became home to the Giordano Furniture company, which — in addition to cranking out hope chests, cedar wardrobes and the like — produced an estimated 1 million wooden ammunition boxes for the boys fighting the good fight overseas.

Then, in late 1948, the wall surrounding the property came down. It was the first act in what would be the demolition of the entire complex.

But also, for the first time in as long as anyone could remember, the Olivier house was visible to passersby. That prompted an architectural elegy of sorts in The Times-Picayune:

“The ancient dwelling wears an air of desolation. The stately columns of white-plastered brick around the galleries, upstairs and down, are falling to ruin. The windows look vacant-eyed upon a strange world beyond the accustomed brick walls. The dejected-looking banisters around the spacious verandas are falling down.”

A still-empty lot

The building’s unceremonious destruction was an impetus for the formation of the Louisiana Landmarks Society, which continues to advocate for preservation of historical structures.

Shortly after 2005’s Hurricane Katrina, there was talk of rebuilding the Olivier house. Maybe that will still happen one day.

But today, 4111 Chartres — and the block that once housed St. Mary’s — sits empty, cleared of all structures, awaiting whatever comes next.

Sources: The Times-Picayune archive; New Orleans City Guide, 1938; Historic American Building Survey; holycrosstigers.com.

Do you know of a New Orleans building worth profiling in this column, or just curious about one? Contact Mike Scott at moviegoermike@gmail.com.