“When you look good, you feel good—and you’ll do good.”

If I had a dollar for every time I heard my father say those words, I could probably buy myself a brand-new…. Well, just know that he said it—a lot. I find myself repeating it often as an adult, even three decades since his passing. It is in those moments that I’m reminded of how much my father’s personal style informed my choices and continues to help guide me. It has impacted how I want to live my own life, and perhaps more importantly, how I don’t want to live it.

When I learned that the theme of this year’s MET Gala is dedicated to Black Dandyism, I chuckled, and wondered what my father would have said about the “homage.” My Dad was a bit of a contrarian at times, regularly challenging the establishment, especially in relation to all things Black culture and artistic expression. I imagine that he would have dissected the very name, Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, which would have likely led to us having layered conversations around the topic before checking out the exhibit together at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

My father was born in Mobile, Alabama, during the Great Depression. He never met his own father, and my paternal grandmother did domestic work for a living. To say the least, his childhood wasn’t rosy.

I vividly remember my dad telling my older brother and me how it was expected for a Black person, even a child, to cross the street in Alabama if a White person was approaching them. Let that sink in.

In his adolescent years, he moved to Philadelphia and later to New York City, where he completed high school. He quickly learned that the racism and inequalities weren’t as blatant as they were in the Jim Crow Era South, but they certainly still existed above the Mason-Dixon Line. Upon arriving in The Big Apple, my father’s artistic talents were nurtured at The School of Industrial Art (now known as The High School of Art & Design). In 2025, this is still a challenging institution to be accepted to, but as a Black teenager from Alabama in the 1950s, it would have been a bona fide feat.

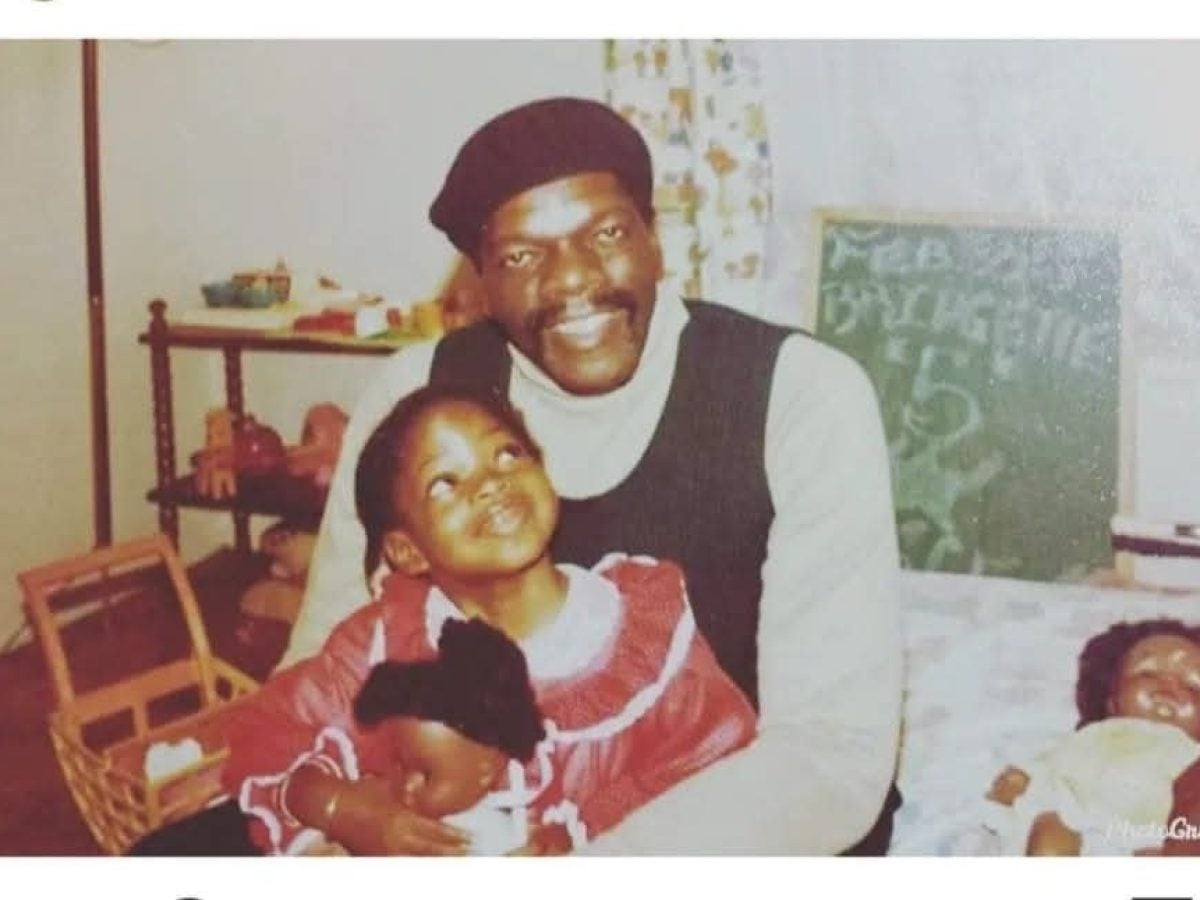

After graduating from high school, Daddy joined the Marine Corps. He was undoubtedly a talented artist, but the career options for him to make a decent living using those gifts were virtually nonexistent. After his stint in the service, he worked several jobs, including being a mail carrier with the U.S. Postal Service and holding a position at the NYC Transit Authority. He worked for the latter as an MTA subway conductor for 20+ years, when he passed away from lung cancer during my freshman year of high school. Even while working a blue-collar job, which required him to wear a (fairly unmemorable) uniform, my dad’s personal style managed to show up in everything about him. He was almost always in a hat—from berets to baseball caps. Even when he was at work, that hat was going to somehow be cocked to the side just so—you know, that signature way only a Black man can rock a headpiece. My love for hats is definitely because of him.

Speaking of work attire, my first “job” was ironing Daddy’s work shirts. I received 75 cents for every shirt I ironed. Since my father worked a hefty amount of overtime, I averaged about $7–$8 a week. That was not a bad gig for a youngster in the 1980s. In addition to keeping me gainfully employed, he also showed me how to iron. Prior to that, I had zero ironing experience. It was my father who taught me that the shirt cuff doesn’t get a crease and schooled me on how to press it separately from the rest of the sleeve.

He also showed me how to properly shine shoes. His was a three-step process: First, we brushed the shoe to get it primed for the polish. Next, we used one of his old undershirts to apply polish in a circular motion to the leather. Then, we used another brush (he had several) back and forth to achieve a desired shine. I’m tearing up now thinking about those lessons because they were much deeper than shining shoes or ironing shirts. In between his meticulous instructions, he would share priceless stories about his life. We were bonding. I didn’t realize how valuable those moments were then. But I do now.

Of course, true style is much deeper than what we wear. My father purchased personalized stationery for me when I was in second or third grade. Even today, I adore receiving and giving handwritten notes on beautiful paper. He also taught me calligraphy.

My father was my first example of a man with layers. He wasn’t the guy to fool around with, and those few who tried found out real quick. (I’ve heard some “colorful” stories!) He didn’t play about respect; not just receiving it, but also giving it. And he didn’t play about his family. He ensured our home was filled with original artwork (primarily his own oil paintings), a treasure trove of books, from Seize the Time by Black Panther Party co-founder Bobby Seale to classic works by philosopher and novelist Leo Tolstoy. Daddy loved to read. He devoured the sci-fi series Dune and his copies of Reader’s Digest, to which he had a steady subscription. My mother’s first copy of ESSENCE magazine? It was my dad who picked it up for her. He noticed the new glossy on the newsstand and thought his wife might enjoy it. Funny how that worked out, huh? And his music collection went—correction, still goes—crazy. Our family listened to R&B greats like Aretha Franklin and The Temptations, but also The Last Poets and lots of jazz on every format, from 8-track tapes to a huge selection of vinyl to CDs.

Despite his humble beginnings, my father had impeccable taste. He enjoyed quality and craftsmanship from clothing to jewelry to furniture. However, much bigger than that was how he didn’t allow society’s expectations of what a poor Black man from Alabama was supposed to dress like, talk like or think like limit him. He worked a blue-collar job that paid the bills yet, rarely, if ever, supported his creativity. That didn’t stop him from painting and sketching at home and introducing his children to the arts whenever and however possible. In his own way, he showed me what it means to forge my own path and that it is okay to sometimes take what seems like the longer route. His style also taught me to stay true to my values and keep going despite life’s curveballs. He didn’t let others prevent him from pursuing his creative passions. At least not for long.

Authentic style requires confidence in who you are and your unique talents and gifts, regardless of where you are from, what you look like, or where you work. This type of style is rare. Just like my father.